By Christine A. Scheller

Would it surprise you to learn that every fourth person you meet struggles with a mental health challenge?

Twenty-six percent of American adults experience a diagnosable mental disorder each year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Mental illness affects people of all ages, races, and walks of life.

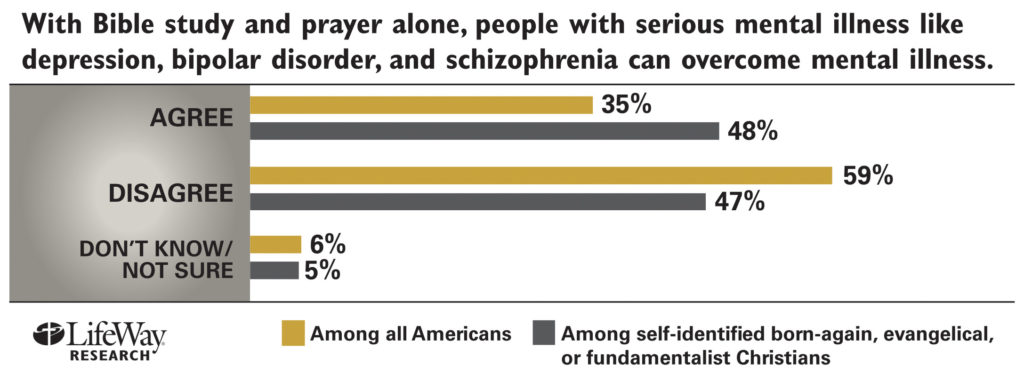

But many church leaders and churchgoers don’t understand mental illness and don’t know how to support sufferers. A September 2013 Lifeway Research survey found nearly half (48 percent) of evangelicals, fundamentalists, and born-again Christians believe that with prayer and Bible study alone people can overcome serious mental illness.

Lifeway Research president Ed Stetzer worries that some Christians see mental illness as a character flaw rather than a medical condition.

“They forget that the key part of mental illness is the word ‘illness,’” Stetzer says.

Compassion for the suffering

Brad Hoefs understands the issue both as a pastor and a person living with mental illness. Hoefs was senior pastor of a fast-growing Midwestern mega-church when his undiagnosed bipolar disorder led to troubling behavior that landed him in the news.

The church was in the midst of a complicated and protracted property purchase. It was the stress of this situation that triggered the crisis, said Hoefs.

The church leadership didn’t know how to respond, however, and Hoefs was let go. A group of 50-to-75 parishioners supported him, paying his salary until he was well enough to return to ministry.

Today, Hoefs has reconciled with leaders from his former congregation and now pastors Community of Grace in Elkhorn, Nebraska, a church he founded with the group who cared for him.

“I believe everybody does the best they can in a crisis like that. However, sometimes we’re inadequate in our ability to respond because we don’t understand mental illness,” said Hoefs.

He compares his manic episodes to being shot up with methamphetamines in the middle of the night: “The next morning you’re all high and crazy and nobody understands why.”

Accountability has been key to Hoef’s recovery, he said. Both his wife and a small group of friends have his permission to talk to each other and to his doctor about his condition.

For the past 11 years (ever since a second stress-induced crisis), he has met every other week with this group of friends.

“It really helped me know that the people who loved me were not just picking on me with my behavior. When your brain is playing tricks on you, you perceive one thing to be reality and sometimes it’s not accurate,” said Hoefs.

For Brian Brodersen, senior pastor at Calvary Chapel of Costa Mesa, California, exercise and a strict diet—along with prayer, meditation, and sometimes medication—have helped him manage occasional bouts of depression and anxiety caused by Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

“Many Christians don’t understand the true nature of mental illness,” says Brodersen. “A lot of Christians think it’s just a matter of wrong thinking patterns that need to be corrected by Scripture and prayer.”

While sin and disobedience may be the source of some mental suffering, that is much different from mental illness, he says.

His task as a pastor is to discern whether symptoms are primarily spiritual or physical in nature, or perhaps a combination of both, and then to respond accordingly.

After Rick Warren’s son Matthew died by suicide last year, Brodersen published a statement in support of the Warrens and those who suffer from mental illness that affirms medical intervention.

“Having had just a little taste of the torment myself gives me a great compassion for those whose suffering is, at times, unbearable,” says Brodersen.

Stigma and misconceptions

The stigma of mental illness can cause some Christians to suffer in silence, even in church.

In her book, Troubled Minds: Mental Illness and the Church’s Mission, author Amy Simpson shares her experience of growing up with a schizophrenic mother.

Asked what has surprised her most as she’s promoted the book, Simpson says it’s the number of people who have said they identify with her story because it mirrors their own in some way.

“People really do want to talk about their own stories and haven’t necessarily felt permission to do that before. That’s been true with lay people and it’s been true with church leaders,” says Simpson.

Christians’ responses to those with a mental illness reflect a combination of the unique kinds of stigma that show up in churches and ignorance about mental illness, says Simpson.

The Lifeway survey found that 54 percent of Americans say churches should do more to prevent suicide. But those who never attend church are the least likely to agree that churches welcome those suffering with mental illness, while those who attend weekly view these houses of worship as welcoming.

Simpson says the big problem is dissonance between the potential and the reality of what churches can offer to those with a mental illness.

“Sometimes that gap is also between reality and people’s expectations,” she says. Even people who never attend church expect churches to help.

A place for caring and support

A broken mind is different from a broken body and how to heal the mind is still more of a mystery than how to heal the body, says Doug Ronsheim, executive director of the American Association of Pastoral Counselors.

“Sometimes we want to address the most complex issues with the simplest answers, because then we feel we have done something,” he says. “So, if you prescribe prayer and it doesn’t work, then you’re not praying right. . . . It puts the onus on the person who is coming to you for prayer. But Jesus says, ‘I’ll walk with you, I’ll talk with you, I’ll be with you in your depths of despair.’”

Ronsheim is a board member for Pathways to Promise, an interfaith resource that helps congregations enhance their capacity to respond to mental illness.

“We really talk about how to be with people, how to be companions with people, not walking behind or walking in front, but how do you walk beside people?” he said.

Pathways to Promise has developed a model for training congregations and faith leaders to do this and to connect congregants with service providers in their communities.

“The congregation becomes a place of caring, support, companionship, but also supports the need for aftercare programs, med visits, all the things that are needed,” says Ronsheim.

Frustration over not being able to find a faith-based support group specifically geared toward mental illness led Hoefs to found Fresh Hope, a network of support groups grounded in Christian hope and a pursuit of wellness rather than merely coping.

At Calvary Chapel of Costa Mesa, plans are underway to launch a support group for both those experiencing mental health challenges and their loved ones, says Brodersen.

For Simpson, the place for churches to start is with a good theology of suffering, one that includes mental illness as a normal part of the human condition rather than something that happens to other, “scarier” people.

“A serious study of Scripture will teach us that we should not be surprised by suffering,” says Simpson. “More churches need to be honest and open about that.”

Churches can and should create boundaries for people whose behavior is disruptive or dangerous, but they should also be consistent, loving, and clear in how that message gets communicated, Simpson says.

“It’s important for churches to think about what they do and do not tolerate, what they are and are not willing to handle within their congregation, and to be reasonable about that,” she says.

A mental health diagnosis doesn’t have to mean a person’s life is effectively over or that God can no longer use them, Simpson adds.

“Medically speaking, there are many reasons that’s not true. So we, the church, can offer hope.”

Christine A. Scheller is a widely published journalist and essayist. She lives with her husband at the Jersey Shore, and in Washington, D.C., where she helps facilitate dialogue between scientific and religious communities.