By Bob Smietana

Mike Waddey began praying the minute he pulled into the parking lot at First Baptist Church in Maury City, Tennessee.

Waddey had come to Maury City (population 665) to interview for the role of pastor at First Baptist. He was familiar with church life in rural America, having been a pastor in Cottage Grove, one of the smallest towns in the state.

But Maury City was going to be different.

From the parking lot, Waddey noticed about 100 people gathered in a park across the street. That was more people than the population of Cottage Grove.

Most of the folks were Hispanic. And Waddey didn’t have much experience with cross-cultural ministry. So he started asking God for help—even before he was called to First Baptist.

“I don’t speak Spanish,” he prayed. “And if there is a large Hispanic community here, I want to be able to reach them.”

Not long afterward, Waddey’s prayers were answered.

One of the first people he met after becoming pastor at First Baptist was Zerafin Guardian, the pastor of a small multi-ethnic church looking for a new home.

The two decided their churches would team up. Today First Baptist is home to two thriving congregations, both trying to share the good news in a small town that needs it.

Places in rural areas—like Maury City—tend to get overlooked these days. People either assume it’s God’s country—where everyone already goes to church and life is like it was in the 1950s—or it’s a version of Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir that tells the story of a family and culture ravaged by opioids and joblessness.

But most of these areas don’t fit neatly into either category. In some places, churches are thriving. In others, there’s a veneer of religion—where people believe in God, but few have any tie to a local congregation.

Here in Maury City, it’s somewhere in between, says Waddey.

People still want to come to church, he says. But they don’t always show up or have a way to get there. And the surrounding county is becoming more diverse—so there’s a need for new ministries to reach new groups of people.

But Waddey maintains it’s still a great place to be a pastor. “Jesus is still a draw,” he says.

Giving up on his dream

Waddey never expected to be a small-town pastor.

He grew up near Franklin, Tennessee, and spent his formative years in a suburban church. When he got the call to ministry, Waddey thought he’d become a church planter. Or maybe a youth pastor.

Then he finished seminary. The only call he got was from a church in a place he’d never heard of.

“I looked on the map,” he says. “Cottage Grove wasn’t on it. That’s how small it was.”

So Waddey and his family went to a town of 88 people, where he learned to love rural ministry. And he learned some humility.

In a small town church, the pastor does everything.

For Waddey, that meant serving his congregation, spearheading an effort to save the town’s post office, and eventually becoming mayor.

It also meant cleaning out the leaves that cluttered the stairwell leading to classrooms in the church basement.

At first, he was angry. Waddey had spent years in seminary preparing to be a pastor only to wind up raking leaves.

Then he laughed. At least the leaves don’t talk back, he thought.

At that moment, Waddey realized he had to be humbled to be effective in ministry. Being a pastor is about serving. Not about being important.

“God knew I needed some humility—and so He took me to Cottage Grove,” he says.

“There’s no better place to learn humility than the smallest incorporated town in Tennessee.”

In those early years, he also learned how to get a lot done with a little bit of money. And he found creative solutions to a community’s problems.

Small town churches know how to do both, he says. That’s how they’ve managed to survive for so long. And how they meet the needs of people in the community.

First Baptist Maury City, for example, has teamed up with other local churches to run a community thrift store and mission, where they sort through donated clothes and other items to determine what should be sold.

The proceeds from the sales are used for a community benevolence fund.

When someone needs help buying groceries, paying the rent, or paying their utility bills, they call Sissy Davis, who founded the mission about eight years ago. Some of the funds also go to help the local Christian school.

The mission started after Davis was up one night praying. She knew the local Christian school was having money troubles. As a pastor’s wife, she was often getting calls from people in the community who needed help.

At about four in the morning, the idea for the mission came to her. She wrote it down and started talking to people about it the next day. Most of the local churches got on board, helping out with donations and volunteers. Church members, and some of the local pastors, like Waddey, shop at the mission as well.

“We get super nice stuff,” says Davis. “I mean the Lord keeps blessing every week. I tell people, ‘When you buy from us, you are blessing someone else. Your dollars help put food on someone else’s table. Or keep their lights on.’”

Sometimes people call and ask for help. Other times, a pastor or other church leaders will let Davis know that someone from their church or in their community is having a hard time. She says some don’t want to ask for help, even if they need it.

Sales at the mission took off when a volunteer’s daughter started a Facebook page for the thrift store. She posts pictures of newly donated items to give customers an incentive to shop.

Davis says the mission would never work without the help of volunteers. She’s glad people from different denominations are willing to pitch in. That kind of community spirit helps hold the town together, she says.

“Lots of those women who volunteer don’t have money to donate,” she says. “They couldn’t give me a $20 donation but they go down there to the mission and work their socks off.”

Still, she worries about the town’s future. Like many communities, Maury City and the surrounding county have been hard hit by the opioid epidemic. She tries to help people affected by opioids—especially if they have kids.

“Little children are innocent,” she says. “They can’t help who their parents are or what their parents are doing.”

But she’ll rarely give out cash.

Instead, she’ll pay directly for someone’s electric bill or medicine. And she’s got an arrangement with the local grocery store. She’ll send someone to the store where they can get $40 or $50 worth of groceries and the mission will pick up the tab.

By working together, Davis says, the local churches accomplish more than they could on their own.

Friendly partners

A great example of doing more together is First Baptist’s partnership with Iglesia Bautista Vida Nueva (New Life Baptist Church).

Ironically, Vida Nueva’s pastor hadn’t planned to be a small town pastor, either.

Zerafin Guardian—also known as “Mister Z”—and his wife, Teresa Guardian, relocated to Maury City about 12 years ago.

They had spent a decade living in Michigan, but had to move for health concerns after Teresa was in a serious crash.

Doctors had to piece her bones back together with steel plates. Even after she recovered, the cold of Michigan made life miserable. So they moved south to Maury City, near Teresa’s parents.

“This is a better place for me to live with all the gear I have in my body,” Teresa says.

Coming to Maury City was like coming home. The Guardians had family nearby and lots of fond memories. They’d met here while working at the local PicSweet Farms when Teresa was on summer break from college.

After moving back, both took jobs in the local school system. Zerafin is a custodian; Teresa works in the school health department.

Things were hard at first. Making friends took time. And then there were the accents. Many folks nearby have thick Southern accents, which hasn’t always been easy for the Guardians, both from immigrant families, to understand.

But they made it work and became beloved in the community.

A few years ago, they felt called to start a church. Both had come to faith as adults and wanted others to have the same experience. In January 2013, they held the first service at a local school.

Their new church continued to meet at the school for two years, growing a multiethnic congregation of about 60 people, with bilingual services in English and Spanish. Zerafin preaches and pastors the church. Teresa leads worship.

The youth group, in particular, thrived—drawing about two dozen teenagers on Friday nights.

When the school district stopped renting space to churches, the congregation at Vida Nueva needed a new home.

A friend introduced Zerafin to Waddey and an instant friendship was born.

Today, Vida Nueva meets on Sunday afternoons at First Baptist, and the two congregations have developed close relationships. When Waddey and his wife adopted their daughter from China, the Guardians and their congregation sold more than $2,000 worth of tamales in a fundraiser on their behalf.

Waddey says church members are glad to host Vida Nueva, especially since Zerafin and Teresa were the leaders.

“They are beloved,” he says.

The Guardians hope their congregation will one day have a home of their own. For now, they are glad to partner with First Baptist.

“We want to reach people for God,” says Zerafin. “That’s the most important mission we have.”

Teresa says she hopes small congregations like Vida Nueva can inspire other, larger churches.

“Our hope is that bigger churches will look at what little churches do and see that they can do the same things—or even more.”

Jesus is still a draw

Before Waddey arrived, the growth of First Baptist Maury City had been plateaued for a while.

The former pastor suffered from cancer, and the church had rallied around him and his family. Helping their pastor through the crisis became the focus of the congregation.

Church members eventually helped his family move to nearby Jackson when he was no longer able to stay in the ministry.

“They loved their pastor through all that,” Waddey said. “That’s one of the reasons I felt comfortable coming here. I knew they would take care of my family. That’s important when you have eight kids.”

Having a new pastor in place has allowed the church to refocus on ministering to their neighbors. Attendance in Sunday school has doubled in size since Waddey arrived—and now averages about 80 people. Around 120 people come to services each Sunday.

Money can be an issue. Some of the newcomers are learning how to give, says Waddey. And older members don’t always have a steady income.

“There’s not a lot of money in rural America,” he says.

The church still has a parsonage, which helps. Waddey and other church leaders keep a close eye on the budget.

It’s a constant balancing act: The church wants to treat their pastor fairly, but they also want to mobilize ministries of the church.

If most of the budget is tied up in a pastor’s salary, says Waddey, that can hurt a church. “If you don’t have money for ministry, then your hands are tied.”

These days, church members do a good job of inviting their friends, says Waddey. And when newcomers arrive, church members make them feel welcome.

The church also started a new Sunday school class when Waddey began as pastor—that’s been a draw as well. New people feel like there’s a place for them.

And often, newcomers to the church will find a friendly face in the pews.

“In Maury City, you don’t have a lot of people who are moving in from somewhere else,” he says. “What you have is a community filled with lifelong relationships. Even if someone has never been in your church—chances are they still know your people.”

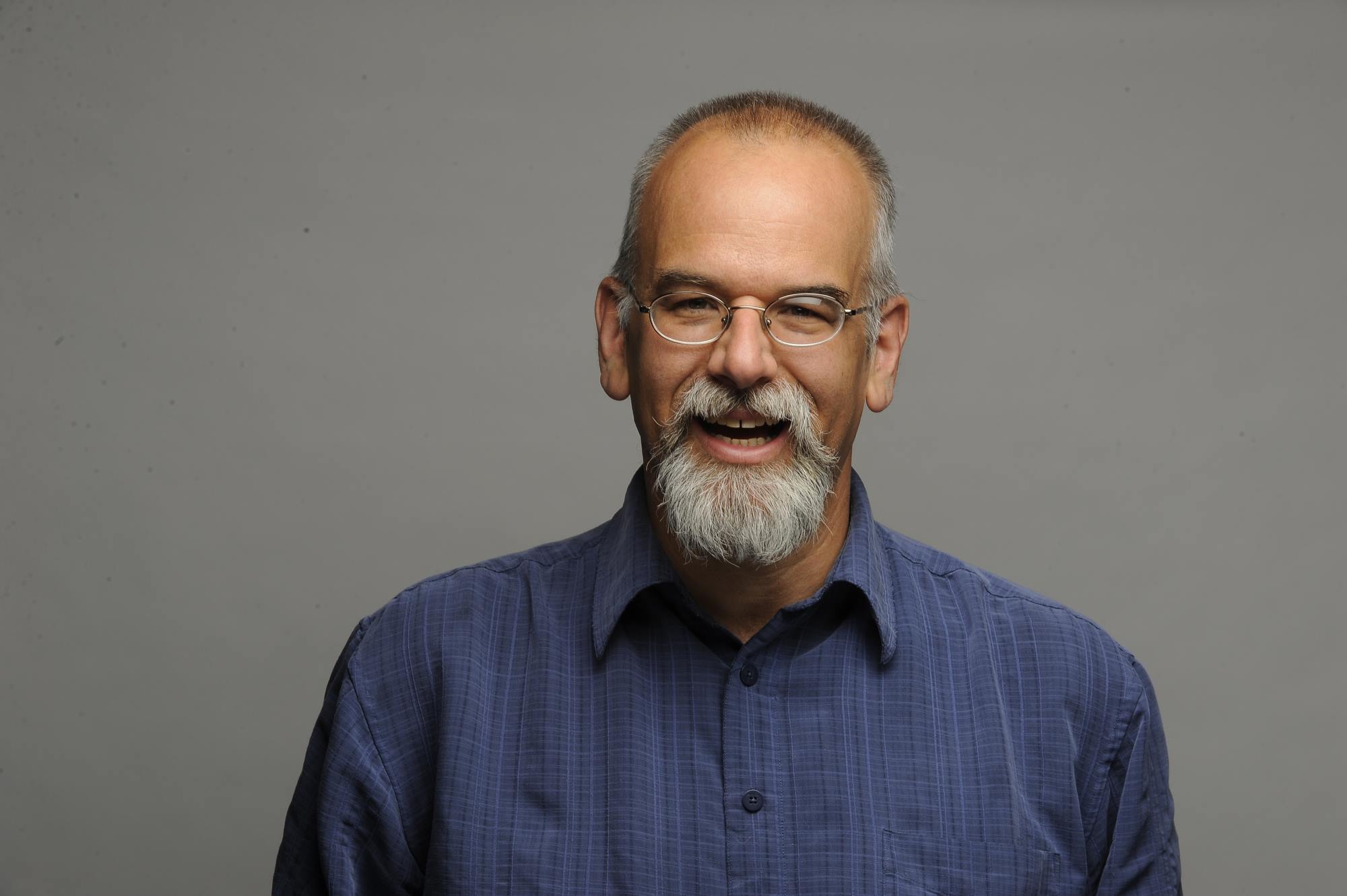

Bob Smietana

Bob is the former senior writer for Lifeway Research. In September 2018, he joined Religion News Service, where he currently serves as a national writer.