By displaying and declaring the unifying work of Christ embodied through the church, local congregations can be an oasis in a world thirsty for harmony.

By Aaron Earls

On the evening of February 28, 1983, most of America came to a halt for the most important event of the year.

“School board meetings, athletic contests and civic events were canceled,” according to The New York Times. “On college campuses, studies—even in the throes of midterm examinations—were forgotten.”

What could draw an entire nation together like that? The final episode of the long-running television series M*A*S*H. That one show united Americans of all backgrounds—at least for a water-cooler conversation the next day.

Today, the illusion of a common culture has fragmented. What lies underneath has been exposed as isolated parts often warring against one another and actively working to avoid those who are different.

If we are honest, churches have not always been an example of unity. There’s a reason Martin Luther King Jr. and others have said Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in the nation.

Yet the church has a biblical command to pursue unity. We also have a heavenly vision of the ultimate fulfillment of that pursuit.

The church can and should fill that role in culture, but it won’t be easy.

A Nation Divided

Many have concluded our nation is hopelessly divided. Looking at much of the evidence, it’s hard to argue.

Red states and blue states not only vote differently in the presidential election but also often view issues from completely contrary perspectives. In urban areas, different racial communities have vastly different experiences within the same city limits. Generations often appear antagonistic toward one another as age groups jostle for cultural power.

The split is obvious in politics. Before the 2016 election, according to Pew Research, 47 percent of Hillary Clinton supporters said no close friends supported Donald Trump, and 31 percent of Trump supporters said no close friends supported Clinton.

Divided over politics, religion, and race, people now watch TV shows targeted to niche audiences. Even within individual families, the kids could be watching YouTube while Dad watches a football game and Mom streams a movie on Netflix.

Social media, which ostensibly is where we should be exposed to varying opinions, has instead made matters worse. Pew Research found only 6 percent of whites but 24 percent of African-Americans say most of the posts they see on social media are about race or race relations.

A Wall Street Journal analysis of Facebook data found that when people from across the political spectrum discuss the same issue online, they see strikingly different stories being shared—virtually all of which support an individual’s preconceived political ideas.

In The Big Sort, journalist Bill Bishop explores how the economic freedom and safety of America have allowed people to segregate themselves into increasingly homogeneous communities.

This type of sorting is unprecedented, says Mark Mulder, sociology professor at Calvin College. “We’ve never experienced this much mobility and choice of where we live, shop, and play.” Many will drive across town to shop at the store they’re used to instead of visiting the unknown store across the street.

What About the Church?

Bishop illuminates an alarming reality: Churches not only participate in this division but in many cases lead the charge. “American churches today are more culturally and politically segregated than our neighborhoods,” Bishop writes. Citing social research, he finds most churches aim for cultural conformity.

Evangelizing unreached people groups through those who share the same language and customs is a technique missionaries discovered on the field, he says. But in America, churches turned the missionaries’ ideas into marketing principles designed to draw in a target audience of likeminded congregants.

In turn, churches have turned loyal members into customers who will shop around to find a church full of similar people. “It’s been proven,” Mulder says, “that homogeneous churches tend to grow and thrive.” Most churches are homogeneous and like it.

“The goal of the church in other times was to transfigure the social tenets of those who came through the door,” Bishop writes. “Now people go to church not for how it might change their beliefs but for how their precepts will be reconfirmed.”

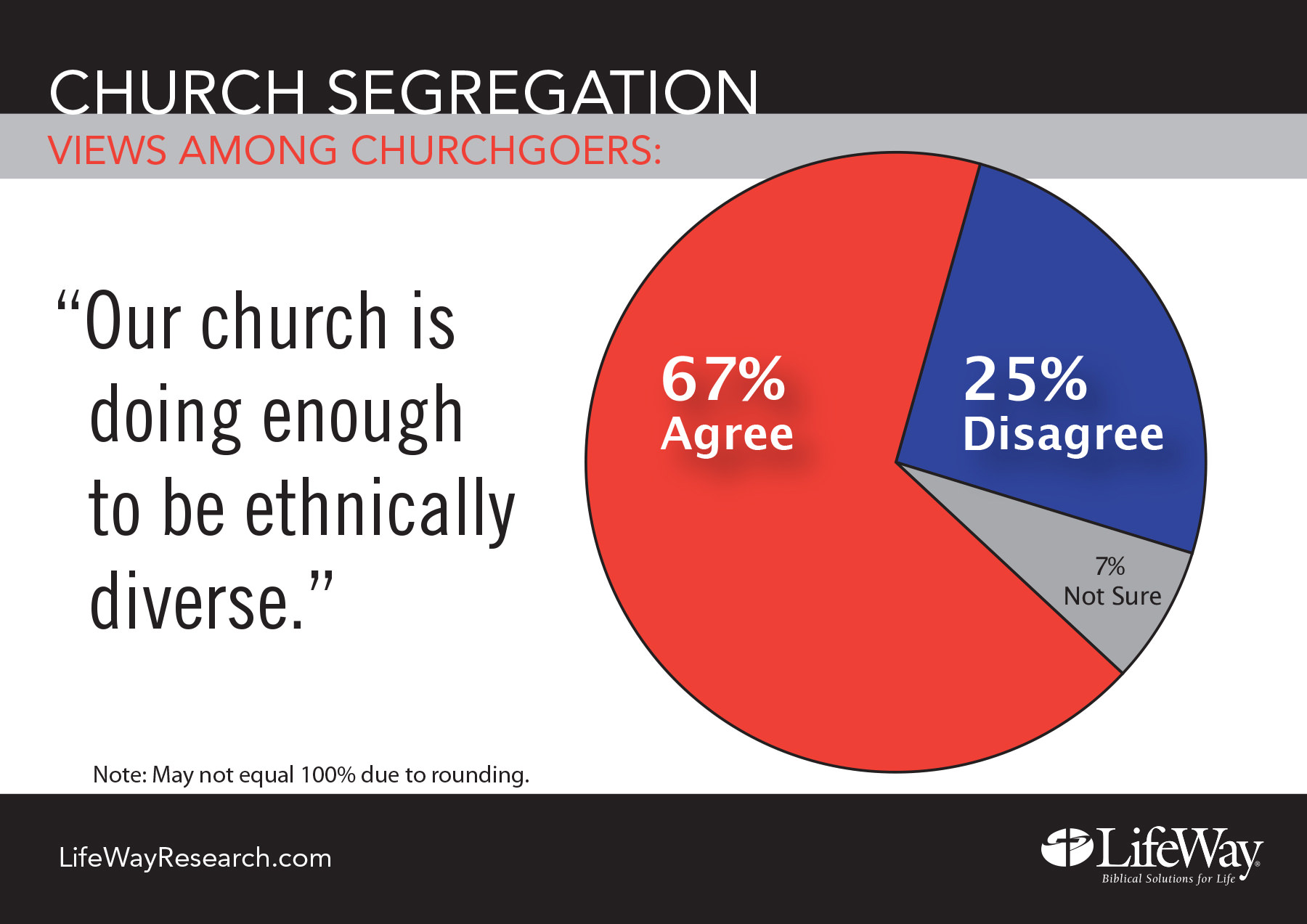

Lifeway Research found 8 in 10 congregations are made up of one predominant racial group. Yet most churchgoers believe their church is just fine. Two-thirds (67 percent) say their church has done enough to encourage diversity.

Only 4 in 10 feel their church needs to become more ethnically diverse. Evangelicals (71 percent) are most likely to think their church is diverse enough, while whites (37 percent) are least likely to believe their church should become more diverse.

This is not necessarily surprising, says Mulder. “When they have a choice, people tend to want to be around people who are as similar to them as possible—it’s terribly affirming,” he says.

And local churches have consistently chosen to be homogeneous. They’ve been content to reach out to people who look and think like those already in the pews, but Steve Patton says churches have a greater calling.

“The church has the full responsibility to encourage diversity in the body like no one else on Earth,” says Patton, a writer and pastor at Reach Church in Kirkland, Washington.

In Revelation 7, Patton says, we see what the church is intended to be. “John said he was shown heaven and in it he saw an innumerable multitude of people from every nation, tribe, and tongue,” he says.

“Diversity in the body is visible in heaven—notice John actually saw their color in heaven; it isn’t color blind—and should be fully visible on Earth.”

Walter Strickland, special advisor to the president for diversity at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, also points to Revelation 7 as the goal. “The church is the centerpiece of God’s missional work in creation, and it is entrusted with demonstrating the unity and diversity that is in store for us in the kingdom,” he says.

Churches content to remain homogeneous “miss what Christ died to achieve. He died to restore all that was broken in the fall, which includes the relationships that each person has with their brothers and sisters in Christ.”

The Way Forward

Reflecting the diversity of heaven and being part of the restoration of creation can seem like an overwhelming task for a local church. But there are steps pastors and church leaders can take to make these ideas more of a reality in their local congregation.

1. Engage with those who are different. “Knowing we have a tendency to create homogeneous groups, churches must be more adept at speaking to a variety of listeners,” says John Hawthorne, professor of sociology at Spring Arbor University.

He maintains churches must be cautious about assuming others are “like me,” while striving to understand them.

Embracing diversity often begins by working with other churches in the community. Scott Sauls, pastor of Christ Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, says a core value for his church is to “form relationships with congregations and ministers of color in our city.”

He and a local African-American pastor have developed a friendship and have preached at each other’s churches.

2. Explore your community. Another step may be examining the surrounding community to see whether the church closely mirrors it. “To whatever degree possible, churches need to reflect the demographic of the community around them,” says Sauls. This requires church leaders to be intentional.

Strickland offers a rule of thumb for churches. See how far local people typically travel for groceries or gas—that’s the size of community your church should reflect.

If someone in your town normally drives 10 minutes to get groceries each week, drive 10 minutes in every direction from your church to discover all the demographics that should be present in your congregation.

3. Look at your leadership team. “The minority groups in the surrounding community must have representation both behind the microphone and at the leadership table,” says Sauls, author of Befriend: Create Belonging in an Age of Judgment, Isolation, and Fear.

“This applies not only ethnically but also generationally, culturally, politically, and socioeconomically.”

Patton agrees leadership and staffing are important, but “hiring an ethnic minority won’t necessarily make you aware of your own cultural norms that accidentally create barriers for others.” That takes personal involvement, he says.

4. Build intentional relationships. “Friendships cause you to take inventory,” says Patton. His advice to church leaders: “Intentionally strive to make genuine friendships with people of different backgrounds.”

Those relationships can take leaders beyond mere tolerance of others who are different to a place of love. “Love is active, outward, and intentional,” says Patton.

That new loving mindset comes from growing as a Christian. “There is no substitute for being mature in Christ,” says Strickland.

“Only those who have spent much time with Christ and in His word are humble enough to see the desires of another as more significant than their own and to put personal preferences aside to serve their brothers and sisters.”

5. Be ready to make sacrifices. Leaders and church members will often have to surrender their own preferences for the sake of welcoming others. “Minorities should never have to repent of their culture to connect in a majority church,” says Patton.

This requires churches to be open to other ways of doing things. The unifying church can no longer disregard changes by saying, “But we’ve always done it this way.” That shift will not happen at the surface level. It has to go deeper.

Mulder maintains it will require sacrifice on the part of leaders and congregants if a church wants to be a cultural unifier.

People like to have their cultural perspectives reinforced rather than challenged, so pastors and leaders seeking to shift from a homogeneous church must also be prepared to face consequences—one of which might be resistance from church members.

Prayer for Unity

As Jesus faced the cross, His prayer for all of those who would believe the gospel was unity. “May they all be one, as you, Father, are in Me and I am in You. May they also be one in Us, so the world may believe You sent Me” (John 17:20).

Knowing His message would soon spread from the Palestinian soil to the far reaches of the world, Jesus prayed that His soon-to-be diverse followers would have such oneness that they would echo the relationship He had with the Father.

“Jesus shows us that the way this broken and divided culture would truly come to know the love of God and the truth of Jesus that will save them is through seeing the unity of the saints,” says Patton.

This is what makes Christian community so countercultural, says Hawthorne. “We spend time with those different from us socially, economically, denominationally, politically, culturally, actually engaging with each other, and we experience the work of the church.”

Ironically, this countercultural aspect of the church is appealing to the culture at large. By displaying and declaring the unifying work of Christ embodied through the church, local congregations can be an oasis to a world thirsty for harmony.

The importance of unity cannot be overstated, says Patton. “This issue will stand to be either the greatest black mark against the church or the greatest apologetic in this culture,” he asserts.

“We haven’t headed down a positive path, but we can still turn things around. For the hope of the glory of God among the living, we must strive for unity.”