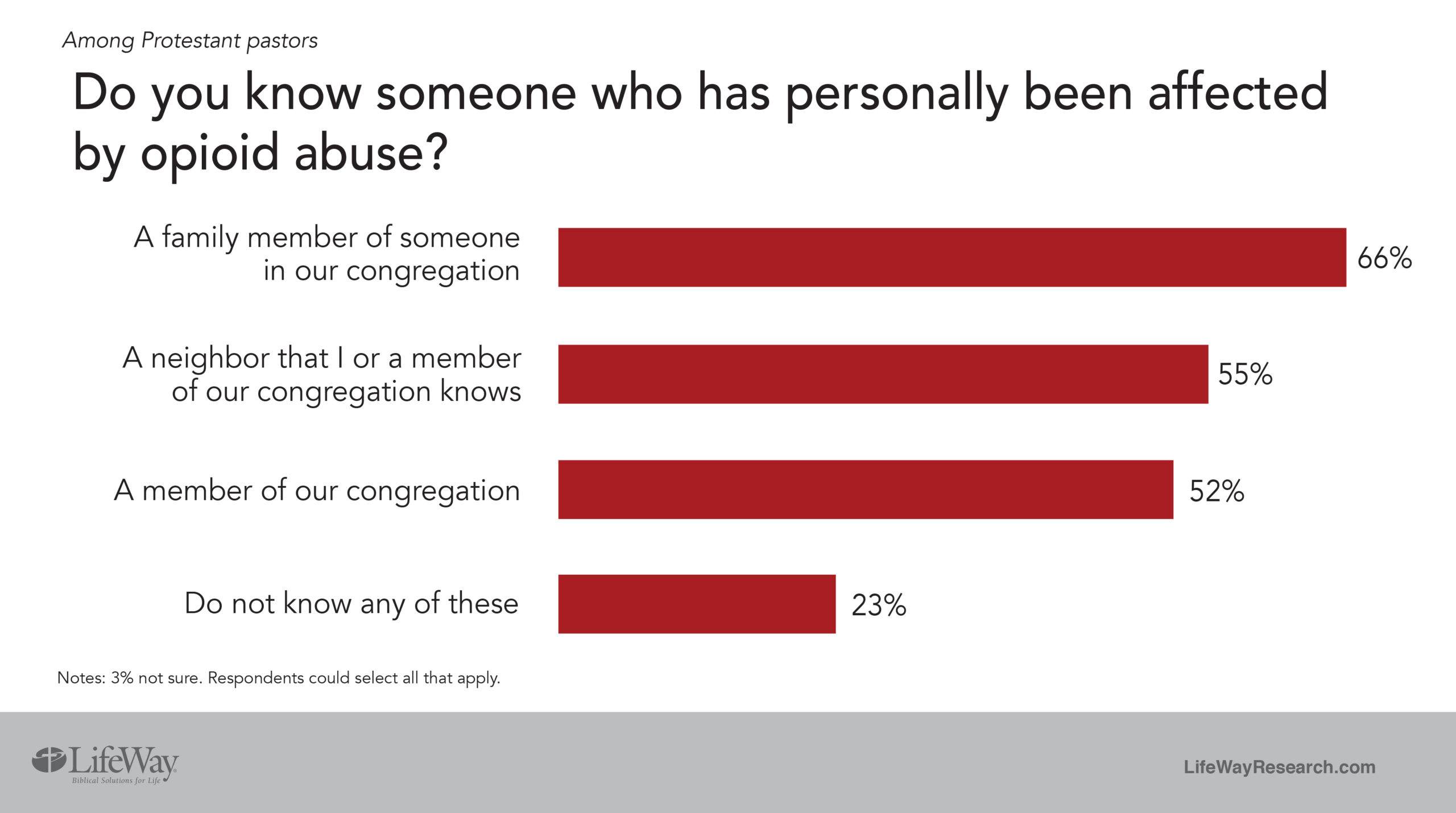

Fewer than a quarter of Protestant pastors (23%) say they don’t know anyone personally affected by opioid abuse.

By Aaron Earls

Like most U.S. pastors, Robby Gallaty knows someone who has been affected by opioid abuse. But unlike most pastors, Gallaty has personally suffered through addiction.

Twenty years ago this month, Gallaty endured a near-fatal car accident. When he left the hospital, the club-bouncer-turned-church-leader took with him several prescriptions for painkillers.

“My descent into full-scale drug abuse was amazingly rapid,” he writes in his new book, Recovered: How an Accident, Alcohol, and Addiction Led Me to God. “In November of 1999, before the accident, I was selling cars, training for the Ultimate Fighting Championship, and thinking about business opportunities. By early the next year, I was looking for faster and better drug connections.”

After stealing $15,000 from his parents to feed his addiction, Gallaty found himself at his lowest point—kicked out of his parents’ home and told not to come back.

“It was the hardest three months of their lives, and they’ll tell you that,” he said. “But it was the best thing for me. I knew that I couldn’t fix myself.”

This led Gallaty, now pastor of Long Hollow Baptist Church in Hendersonville, Tenn., to what he calls a “radical, Paul-like conversion” on November 12, 2002.

Most pastors don’t have the intimate knowledge of addiction Gallaty has, but most say they’ve seen it face to face through people connected to their church and even among members of their congregation.

Nashville-based Lifeway Research asked 1,000 Protestant pastors about their personal connections to the opioid epidemic and how their churches are looking to address the issue.

Two-thirds of pastors (66%) say a family member of someone in their congregation has been personally affected by opioid abuse.

More than half (55%) say they or someone in their congregation knows a local neighbor suffering through opioid abuse.

For half of pastors (52%), someone directly in their church is dealing with an opioid addiction.

Fewer than a quarter (23%) of pastors say they don’t know anyone personally affected by it.

“The drug epidemic has infiltrated our churches and neighborhoods. It is not localized to a particular region or socio-economic class,” said Gallaty. “Addiction is no respecter of persons.”

Pastors of the smallest churches (fewer than 50 in attendance) are most likely to say they don’t know anyone connected to their congregation or community affected by opioid abuse (31%).

Pastors in the Northeast (11%) are least likely to say they don’t have any such personal connections.

“More than two-thirds of even the smallest churches have connections to people affected by opioid abuse,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Opioid addiction can impact people who aren’t a significant risk for other types of drugs.”

Church response

Despite most pastors having a personal experience with someone suffering from opioid abuse, Gallaty said many church leaders don’t know where to start in responding to the opioid epidemic.

“Some pastors are at a loss to understand the issues surrounding personal struggles and don’t have a plan of action to help those in need,” he said.

Unfortunately, Gallaty said some pastors are dismissive of “those drug heads” from a certain area of their town, but he says that attitude is wrong for two reasons.

Being a college graduate with a full-time job and having a good home with hard-working parents means Gallaty didn’t fit those stereotypes. “I never asked to be injured, nor did I intend to get addicted to pain medication,” said the Recovered author. “Still, it happened to me, like it has to so many others.”

Even more importantly, Gallaty said “‘those drug heads are sons and daughters of people in our congregations and communities. They are all made in the image of God and need to know that addiction, like any sin, can be broken through the healing power of the gospel.”

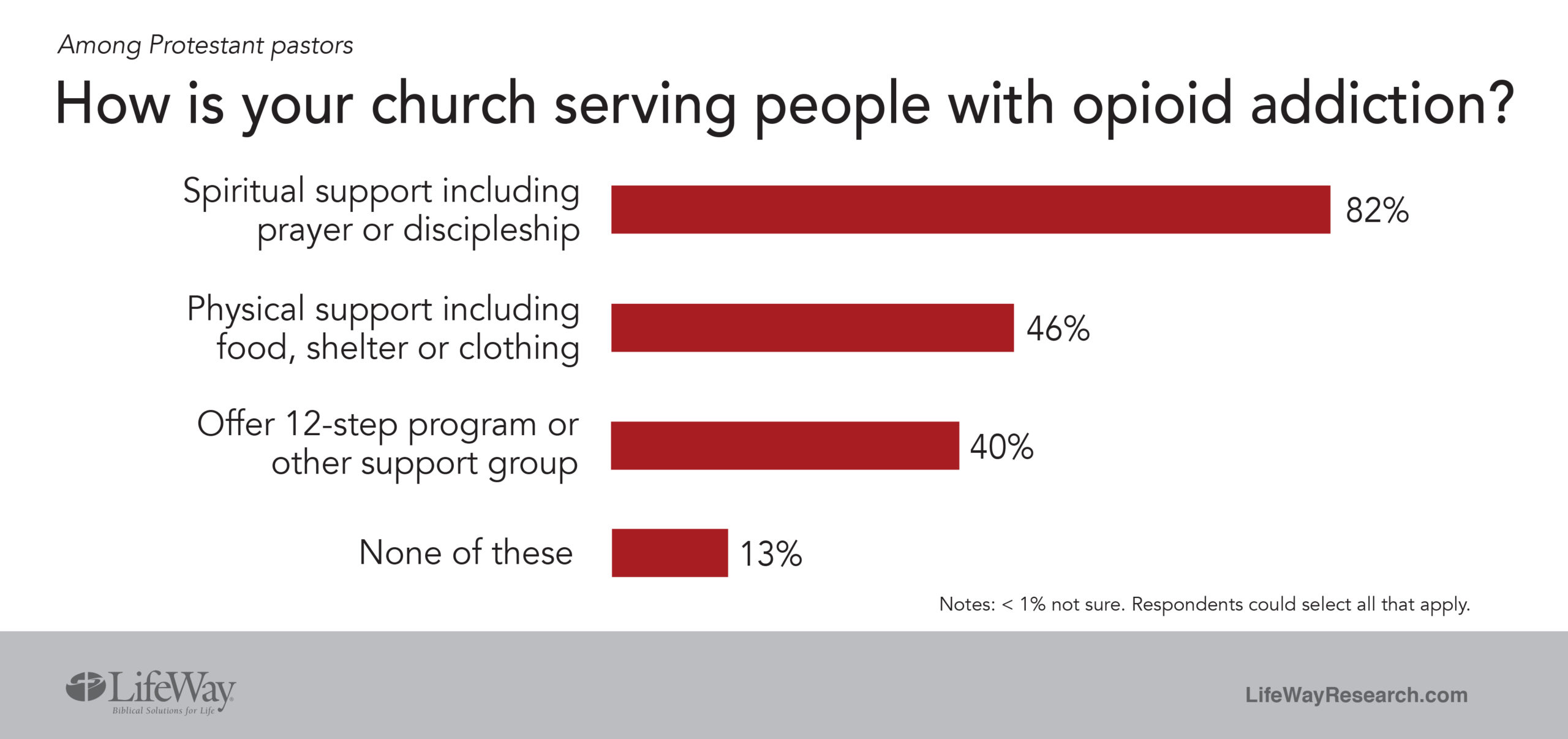

According to the Lifeway Research study, most churches are trying to do something.

Around 4 in 5 pastors (82%) say their church currently serves people with opioid addiction by offering spiritual support including prayer or discipleship.

Close to half (46%) say they offer physical support including food, shelter or clothing, while slightly fewer (40%) offer a 12-step program or other support groups for substance abuse.

Around 1 in 8 pastors (13%) admit their church currently isn’t doing any of those things for people with opioid addiction.

“When churches offer spiritual and physical help to those in their community, they will meet people with many needs that go beyond those offerings,” said McConnell. “Churches have a choice of whether they will address those more complex needs, connect the hurting with help elsewhere, or ignore the needs.”

Larger churches—those with more resources and more personal connections to the crisis—are most likely to say they offer both spiritual and practical help for those with an opioid addiction.

Gallaty said one simple way churches can address the problem is by “educating our people on the dangers of addiction by talking about it publicly and preaching sermons about the topic. Pastors shouldn’t shy away from it.”

As people with addictions come to the attention of the church, however, Gallaty said congregations and leaders must be ready. “When people come to our churches as hospitals for healing, pastors should have a game plan to help them,” he said.

“We can stick our heads in the sand and hope the issue dissolves, or we can recognize the need and take steps to come alongside those struggling.”

Methodology:

The phone survey of 1,000 Protestant pastors was conducted Aug. 29 to Sept. 11, 2018. The calling list was a stratified random sample, drawn from a list of all Protestant churches. Quotas were used for church size.

Each interview was conducted with the senior pastor, minister or priest of the church called. Responses were weighted by region to more accurately reflect the population. The completed sample is 1,000 surveys. The sample provides 95% confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 3.2%. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups.