By Aaron Earls

In times of crisis, there’s nothing Christians love more than a C.S. Lewis quote, real or fake.

Matching the spread of the coronavirus, a passage from Lewis’ essay “On Living in an Atomic Age” went viral in its own way, as Christians shared the words across social media.

In his admonitions, can we simply replace the words “atomic age” with “COVID-19 age” or was Lewis getting at something deeper and even more relevant for the church today?

Lewis’ atomic age

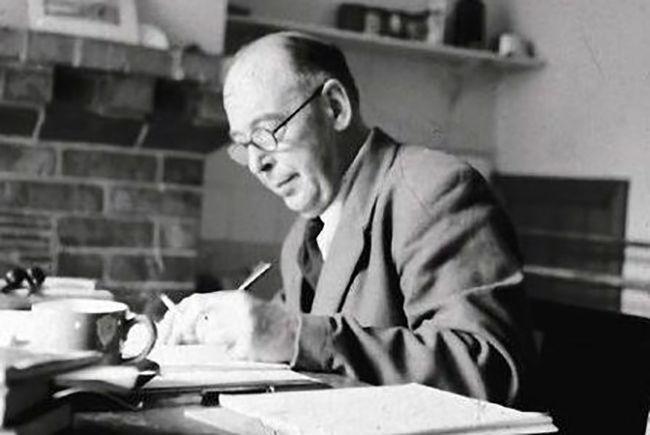

As a Christian apologist, Lewis often spoke and wrote about cultural concerns and how those intersect with Christianity. His famous work Mere Christianity was adapted from talks he gave on the radio.

So it is not surprising that as fears surrounding the atomic bomb grew, Lewis would address them in his writing.

Here’s how he opened “On Living in an Atomic Age,” which can be found in the collection Present Concerns: Journalistic Essays:

In one way we think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb. “How are we to live in an atomic age?” I am tempted to reply: “Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents.”

In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation. Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways. We had, indeed, one very great advantage over our ancestors—anesthetics; but we have that still. It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds.

Some took Lewis’ words as an excuse to discount the warnings of the pandemic.

“We shouldn’t live in fear and quarantine ourselves,” they argued. “C.S. Lewis would tell us to go out and live our normal life.”

Yet, I don’t think that’s what Lewis would want us to take away from his essay. One, it’s not the actual point he’s making (which we’ll address shortly). Two, it’s not how he actually lived during his own national tragedy.

During World War II, the United Kingdom used several national measures that limited personal freedom to assist the war efforts.

If you read Lewis’ letters during those years, he frequently mentions the rationing of certain types of food and thanks many of his American friends for their shipping him some items he couldn’t readily get.

What you won’t find is Lewis recommending people ignore the rationing efforts and for British citizens to simply live as if those restrictions didn’t exist. He understood the importance of societal sacrifice for the benefit of all, but that looks different in different circumstances.

Living during World War II, C.S. Lewis understood the importance of societal sacrifice for the benefit of all, but that looks different in different circumstances. — @WardrobeDoor Click To TweetA proper response to an atomic age would be to live life as normal. Similar to the way Americans were encouraged to go out and resume our daily habits after the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Most of us could not do anything to prevent a nuclear bomb dropping on our city, but we can all do something to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Current self-quarantines and masking recommendations are more reflective of the rationing in place during World War II. They are meant to be joint sacrifices that serve a greater good and seek to keep others safe.

But we should return to the point Lewis is actually making in “On Living in an Atomic Age,” which is even more applicable to our present age than the out-of-context passage being shared on social media.

The result of an atomic age or coronavirus age

After the above excerpt, Lewis moves on to what he saw as the “real point.” The concern about the atomic age (or the coronavirus) undermines atheism or any other naturalistic worldview that sees no room for a supernatural God existing outside of nature.

He points out that all of science agrees that the end of life on this earth is inevitable. It’s only a matter of “when” not “if.”

If the threat of an atomic bomb serves as a reminder for us, then it can be a good thing. “We have been waked from a pretty dream, and now we can begin to talk about realities,” he writes.

Once we are awakened to the frailty of life, Lewis says we see at once that whether or not an atomic bomb destroys civilization is not the most important question. Something was always going to destroy us and civilization.

The most important question becomes: Is this all there is?

If we are doing to die (and we will), if civilization as we know it will be ended (and it will), Lewis argues, then we should be most concerned about what, if anything, lies beyond the natural world?

It is at this point, when we should see how Lewis’ words are applicable to our current situation.

People are scared and looking for answers. The coronavirus is causing them to confront mortality—their own and their loved ones’.

Lewis exposes how a naturalistic mindset leads us to hopelessness or irrationality. As people confront that reality, Christians can point to a better way.

“Mistaken for our mother, [Nature] is terrifying and even abominable,” Lewis writes. “But if she is only our sister—if she and we have a common Creator—if she is our sparring partner—then the situation is quite tolerable.”

The Christian worldview recognizes the existence of evil, even within the natural world. All of creation is groaning as we await our ultimate redemption (Romans 8:22-23).

Because there exists a God beyond nature and we follow His laws rather than nature’s, Lewis says we follow “the law of love and temperance even when they seem suicidal, and not the law of competition and grab, even when they seem to be necessary to our survival.”

In our own day, Christians love our neighbors by working to limit the spread of a deadly disease, while not participating in the hoarding of food and toilet paper.

“We must train ourselves to feel that the survival of Man on this Earth, much more of our own nation or culture or class, is not worth having unless it can be had by honorable and merciful means." — C.S. Lewis Click To Tweet“We must train ourselves to feel that the survival of Man on this Earth, much more of our own nation or culture or class, is not worth having unless it can be had by honorable and merciful means,” Lewis writes.

And as we live life differently—both from how we did previously in limiting our interactions and in how others do now through selflessness—we will have the opportunity to speak of Christ to those who are waking up to the realities of this life.

More than anything else, that is what Lewis—and more importantly, Christ—would have us do in the atomic age, the coronavirus age and every other age in this world.