By Aaron Earls

Less than half of Americans say they belong to a house of worship, marking the first time, since Gallup began collecting data in 1937, a majority aren’t part of a church, synagogue, or mosque.

Religious membership was stable throughout the 20th century but fell from 70% in 2000 to 47% in 2020. While this should cause concern among church leaders, the situation may be less dire than it appears.

In 2020, religious membership dropped below 50% in the U.S. for the first time since Gallup began tracking such information. Click To TweetSo, what explains this significant membership drop? Three factors can help churches better understand the religious landscape in the United States and how to reach their changing communities.

Rise in nones

Undeniably, fewer Americans say they belong to a religion, much less a specific religious institution. According to Gallup, “nones” (those who choose “none of the above” when asked their religious preference), have grown from 8% in 2000 to 20% in 2020. The General Social Survey (GSS) noted an increase from 14% to 23% in the same time frame. Pew Research tracks the growth from 17% in 2009 to 26% in 2019.

It should be noted that the growth is not driven primarily from a jump in atheists or agnostics—both only saw modest 2-point increases in Pew’s findings. Similarly, the percentage of Americans who say they don’t believe in God inched upward from 3% in 2000 to 5% in 2018, according to the GSS. Instead, as Pew’s data found, those who are simply “nothing in particular” climbed from 12% in 2009 to 17% in 2019.

Growth of the religiously unaffiliated in the U.S. does not primarily come from a jump in atheists or agnostics, who only grew by 2 percentage points in the past 10 years. Click To TweetAmong those without a religious preference, Gallup found—as expected—few (4%) say they have a formal church membership. This means that as more Americans fail to identify with a religion, more Americans will choose not to identify as a member of a church.

Institutional rejection

Church membership is falling, but so are numerous other official ties to organizations. Americans are increasingly wary of institutions.

In another Gallup survey, the percentage of Americans who say they have quite a lot or a great deal of confidence in the church or organized religion dropped almost 15 points in the past 20 years. While 42% say they trust the church, that’s down from 56% in 2000. But other groups and institutions have seen significant declines in the past two decades: TV news (18 points), newspapers (13 points), Congress (11 points), big business (10 points), banks (8 points), Supreme Court (7 points), and police (6 points).

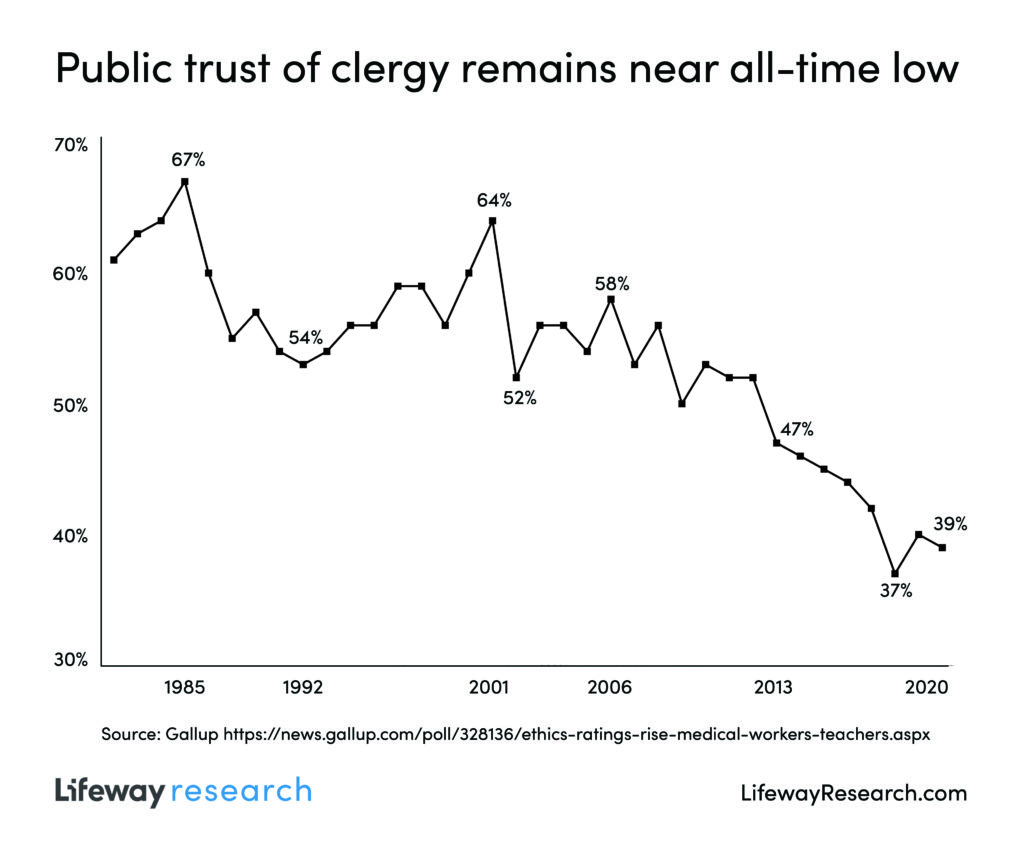

When seeking to add to their membership or even maintain current levels, congregations are fighting an uphill battle against the culture's anti-institution tendencies. Click To TweetSimilarly, Americans don’t trust the leaders of those institutions. Fewer than half of U.S. adults say judges (43%), bankers (29%), journalists (28%), labor union leaders (24%), local officeholder (24%), lawyers (21%), state governors (20%), state officeholder (19%), business executives (17%), senators (13%), and members of Congress (8%) have high or very high honesty and ethics, according to Gallup.

Among pastors, public trust has fallen precipitously since the turn of the century when 64% of Americans gave them high ratings for their honesty. In recent years, that number has fallen below 40%. In the most recent survey, 39% had a positive opinion about the ethics of clergy.

If Americans have a negative view of institutions, including churches, and they lack trust in the leaders of those institutions, including pastors, it is no wonder church membership has dropped in recent years. When seeking to add to their membership or even maintain current levels, congregations are fighting an uphill battle against cultural tendencies.

Church clarity

Growing up, I remember the sign above the piano in our small country church that announced numbers like last week’s Sunday School and worship service attendance, as well as our church membership. While we only hit triple digits on a good Sunday, our membership number always stayed above 300. Many of those in church today won’t have that same experience.

While membership has undergone a precipitous drop, the decline in religious service attendance has been much less severe. Click To TweetWhile membership has undergone a precipitous drop, the decline in religious service attendance has been much less severe, according to Gallup. In 2000, 44% of Americans said they attended a service in the last seven days. That fell to 34% in 2019. In Gallup’s other church attendance measurement, 46% of Americans said they attended a religious service at least almost every week in 2000. In 2020, 33% said the same.

Other surveys measuring church attendance find even smaller declines. According to the GSS, 38% of Americans attended religious services at least two to three times a month in 2000. That dipped only 2-percentage points to 36% by 2018.

The social benefit of maintaining a church membership is disappearing. While there is obviously something lost when a culture drops much of its Christian influence, the church is also granted a clarifying opportunity. Now more than ever, church leaders know who is part of their congregation. As membership numbers decline, they move closer to actual attendance numbers and give churches a more accurate picture of their congregation.

While church membership may be falling, it’s not taking the sky down with it. This should be an opportunity for prayer and faith, not one of panic and fear. — @WardrobeDoor Click To TweetWhile church membership may be falling, it’s not taking the sky down with it. As more nominal Christians become nones and culture continues to avoid institutional ties, pastors and church leaders can see who truly is a follower of Christ and who in their community they need to reach with the gospel. This should be an opportunity for prayer and faith, not one of panic and fear.