Curiosity about how we got the Bible has led many in our churches to wonder whether they can trust it. Here are three reasons we know we can.

by John D. Meade and Peter J. Gurry

If you’re like us, you were probably not informed about how we got the Bible early in your Christian life. But later, you read or heard something about the Bible’s history that piqued your curiosity. Or maybe you began to look down in your own Bible and noticed different readings within verses with unfamiliar terms like “Septuagint,” “Vulgate,” “Masoretic Text,” or the like and you wondered what these could mean.

No doubt, you have read the passages introduced with, “The earliest manuscripts do not include these verses” (e.g., John 7:53–8:11). Whatever the cause, curiosity about how we got the Bible has led many in our churches to wonder whether they can trust it as the rule for our faith and practice.

Here, we provide some historical and theological reasons we can trust our Bible.

1. Biblical manuscripts disavow doubt

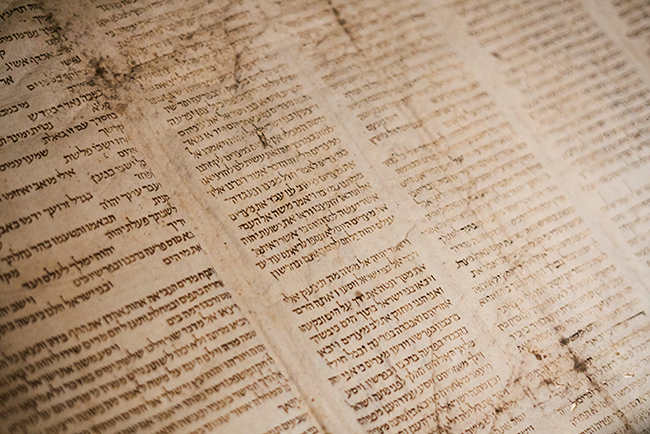

The books of our Bible were written down on scrolls or in a codex and then copied. Those copies were then hand-copied on and on. Today, we have thousands of Old and New Testament manuscripts. In popular imagination, this process is often perceived like the telephone game such that, today, we don’t have the Bible’s original words. The message has been garbled.

But in reality, scribes didn’t copy the scriptures like our grade-school game. They often checked their copies, referenced older copies, and in many cases caught mistakes, though not all of them. More importantly, no one today is reading a Bible based solely on one line of transmission. Rather, modern translations are based on multiple lines. This makes comparison and evaluation possible. As textual critics compare the manuscripts, they decide on the best reading and prepare a corrected text so that we can be confident that what we’re reading is what writers initially wrote, or very close to it.

Popular imagination pictures going from the original manuscripts of biblical books to our Bibles today as something resembling the "telephone game." In reality, the process is not like the game at all. Click To TweetTo give a brief example. In the King James Version, James 2:18 reads “shew me thy faith without thy works” while the margin adds that “some copies read, by thy works.” Modern English translations print “without works” and feel no need to give a note at all. This is because translators today have access to more and better manuscripts than were available to the KJV translators. Their confidence in the original text at this point has increased with time.

2. Canon process engenders trust

If we have greater knowledge about the text’s history today, what about the canon? Can we have confidence we have the right books? Because Jesus is the Good Shepherd, and His sheep hear His voice, we should expect to hear God’s voice in the inspired scriptures of His holy prophets and apostles. But in the Church’s earliest years, there were many different writings alongside the books we know as our Old and New Testaments. Older Jewish works like the book of Enoch and early Christian works such as the Shepherd of Hermas were clearly important books. How did early Christians learn to discern the Shepherd’s voice amidst the clamor of noise?

What they did not do is resort to a single, official list of books. Neither Jesus nor the Apostles left behind a list of canonical books. Nor did an emperor like Constantine or a church council like Nicaea give us the canon of Scripture. This second view, though very popular, is a myth. The canonical process was “messier” but no less authentic because of that.

The list of books included in the Bible wasn't decreed by an emperor or church council. The canonical process was “messier” but no less authentic because of that. Click To TweetWhat is remarkable is that, in the absence of a single decision on the canon by a council or bishop or emperor, all early canon lists mainly agree on what books were divinely inspired: the Old Testament (the Apocrypha was debated), the four gospels, Acts, the thirteen or fourteen Pauline Epistles (Hebrews was debated), 1 John, and 1 Peter. No list included a book like the Shepherd of Hermas, but not all lists included 2 Peter either. Parts of the story are messy.

If a centralized council doesn’t account for the vast agreement among Christians on the books of the Bible, what does? There was probably a strong, early tradition about the church’s core canon on which most Christians had long agreed. And the debates concerned only a few books at the edges. Thus, the overwhelming agreement shows early tradition was at work. And disagreements over a few books at the edges show that the canon didn’t result from a centralized power play. Christians over time kept recognizing the divine qualities of the canonical books. And that’s how we got the books that are in our Bible today.

3. A rich tradition of translation

As Christians copied the Bible and recognized its boundaries, they also saw the need to translate it for Christians who couldn’t read Greek and Hebrew. Following the precedent of the Septuagint, Christians translated the Bible into Latin, Coptic, and Syriac in the first four centuries after Jesus. Other languages followed.

“When we read the Bible today, we are the beneficiaries of a great line of previous laborers.” — @drjohnmeade @pjgurry Click To TweetThat process continues today and presents translators with unavoidable dilemmas that often go unnoticed by readers. These range from which text to translate, to which audience to aim for, to whether they will start from scratch. Other dilemmas revolve around how to handle metaphors, wordplays, and ancient names along with a host of culturally specific terms for plants, animals, monetary values, weights, measures, diseases, and so many more.

Thankfully, English has one of the richest histories of Bible translation from the original languages going back to William Tyndale and reaching a watershed with the elegance of the King James Bible. When we read the Bible today, we are the beneficiaries of a great line of previous laborers.

Resting in divine providence

Christians have confessed that holy men, inspired by God, wrote the Scriptures (2 Timothy 3:16) without error. That’s the true miracle of the Bible’s creation. But Christians don’t usually confess that God has preserved His Scriptures in quite the same way as they were created. Scribes did make copyist errors. But providentially, God used the normal human means of copying the scriptures, acknowledging their canonicity, and translating them in order to provide the church with His Word written. Therefore, normal human messiness is part of the Bible’s history. But we can rest in the fact that God’s providence has orchestrated matters to provide us with what we need.

John D. Meade

John is a professor of Old Testament and co-director of the Text & Canon Institute at Phoenix Seminary. He is the co-author of Scribes and Scripture: The Amazing Story of How We Got the Bible and of The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis.

Peter J. Gurry

Peter is an associate professor of New Testament and co-director of the Text & Canon Institute at Phoenix Seminary. He is the co-author of Scribes and Scripture: The Amazing Story of How We Got the Bible and the author of A Critical Examination of the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method in New Testament Textual Criticism.

If you want to learn more about how we got the Bible, read John and Peter’s new book, Scribes and Scripture: The Amazing Story of How We Got The Bible (Crossway 2022).

For permission to republish this article, contact Marissa Postell.